There was celebration on the pages of the Daily Maverick a few days back ( https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2017-01-10-king-kong-lives-again-iconic-1950s-musical-revival-set-to-be-highlight-on-sa-2017-cultural-calendar/#.WHc1gpHzeIw) over the announcement that Fugard Theatre producer Eric Abraham had secured production rights and “the blessing of those original artists connected with the production who are still alive” to revisit the iconic musical King Kong (launched in 1959) at the theatre later this year. Abraham has pulled in UK director Jonathan Munby and Cape Town musical director Charl-Johan Lingenfelder to “restore the authenticity” of a score watered-down for the London tour of the show.

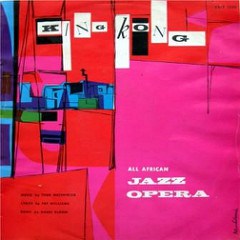

All very heartwarming. Certainly, some things are unarguable: King Kong was an important event for South African music theatre, and for some musicians and audiences worldwide; and Todd Matshikiza’s original score was superb. YouTube, unfortunately, can’t provide a clip of the musical high-spot: Matshikiza’s Hambani Madoda (In the Queue), but here’s the iconic opener, Sad Times, Bad Times, to give you a flavour. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qn7cmLYc9D4

Munby definitely gets what was wrong with the London production. “The West End show (…) feels like just another West End production. All authenticity and originality is lost in an attempt to create a quintessential Broadway sound. There is, in many ways, a cheapening of it all. It is loud, it is bombastic and blown through the roof in terms of scale. It was Westernised in a way now that feels offensive,” he told Maverick journalist Marianne Thamm.

“Now” feels offensive? It was offensive to all the musicians back in the 1960s. When I interviewed him for my book Soweto Blues in 2000, trombonist and King Kong cast member Jonas Gwangwa detailed those criticisms and more: “But of course Jack Hylton got one of his arrangers to come in and say: ‘It’s not quite English; there are some things we have to put in.’ Which I objected to but well, who was I? But I said: ‘You’re spoiling the music.’ [They changed] some orchestrations where we had the trombones going high, as in Kwela Kong, and they always wanted to have the ends of the songs going higher and much louder than we had them…”

But there was more that was offensive, and that’s where the warm wave of nostalgia about the King Kong re-visioning begins to raise more questions than its spokespeople have so far answered. Though the King Kong cast members I interviewed all spoke warmly about some of their white collaborators, and particularly Spike (now Sir Stanley) Glasser, most felt that the entire process of creating the musical had carried elements of patronisation and appropriation, long before the show ever got to London.

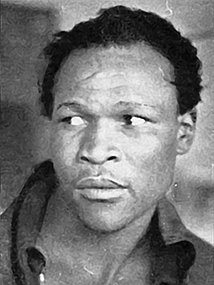

Said Gwangwa: “…it was well done. The problems that arose were…you cannot really tell the truth, you know? It was alleged that [King Kong: boxer Ezekiel Dlamini] committed suicide, but we believed that he was killed in prison and thrown into a dam which was being built. That was one of the bigger problems. And there were some people who were political activists here at home, like Dan Poho who belonged to the garment workers’ union, a devout ANC activist at the time, who they refused a passport. Gideon Nxumalo…couldn’t go abroad. (…) But the main thing was the real story of Dlamini…That was, you know, the whole apartheid South Africa …that couldn’t allow people to tell the real story.”

Composer Todd Matshikiza was scathing about the process in his autobiography, Chocolates for my Wife (http://www.takealot.com/chocolates-for-my-wife/PLID34235975 ) he describes a bitter sense of appropriation:

“I think King Kong will make a marvellous excuse for a theatrical production. Your people are so much alive, especially for this sort of thing…I will put some of the language down as spoken in the township, can you give me a few phrases…what is the lingo?…Let’s get to Rupert’s place and put down as much African lingo as we can…Every night I dreamed I was surrounded by pale-skinned, blue-veined peoplewho changed at random from humans to gargoyles. I dreamed I lay at the bottom of a bottomless pit. They stood above me, all around, with long sharpened steel straws that they put to your head and the brain matter seeped up the straws like lemonade up a playful child’s thirsty picnic straw…I have been listening to my music and watch it go from black to white and now purple.”

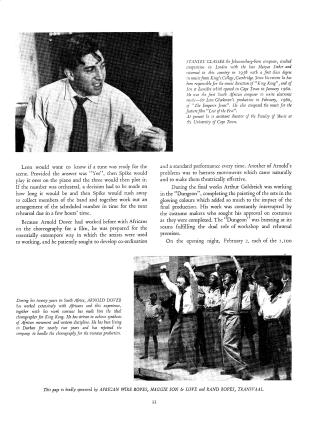

And while there was genuine collaboration too, the title page of the London programme preferred to describe the manful struggle of white directors to ‘tame’ black musicians:

“Because Arnold Dover had worked with Africans before on the choreography of a film, he was prepared for the essentially extempore way in which the artists were used to working, and he patiently sought to develop co-ordination and a standard performance every time. Another of Arnold’s problems was to harness movements which came naturally and make them theatrically effective.”

Nostalgia around South Africa’s musical past can be toxic as often as it is creative. It can take a reductive stance that demands contemporary black musicians play township stereotypes. From what Munby has said, that’s hopefully not the trap he will fall into. But it can also become so overwhelmed by the creativity of the original sound that it fails to interrogate or include in the discourse the exploitative processes around the music’s making.

It’s a little disappointing that so far the team talking about the production to the press includes nobody involved with the original music, and nobody from the relevant community of colour, although these are early days yet. King Kong did have an essentially Black Joburg vibe, even after it was mutilated by Hylton’s arranger, with some of the leading avant-gardists of the day such as reedman Kippie Moeketsi. It drew deep from the vibe of Drum, Dorkay House, the Odeon Cinema, and Orlando…

On the other hand, a production that interrogated the making of King Kong – not necessarily this one, but some production, somewhere – could still give us that glorious music, and also explore tensions and debates that would speak way more powerfully to today’s decolonisation discourses.

0

0

1

956

5452

private

45

12

6396

14.0

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0cm 5.4pt 0cm 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0cm;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-fareast-language:JA;}

Thanks for this Gwen. 1) The Daily Maverick article was ridiculous. Poorly researched and badly written. 2) It is scandalous that nobody has mentioned Esme’s role as custodian of this artwork. 3) Even nostalgia would be better than whatever this is. KK is an African Jazz opera not a musical. Munby is having his cake and chewing it.

It’s disgusting how certain creatives have been profiting from Todd. That a musial genius like TTM is treated so carelessly by public and so-called organic intellectuals. I don’t want to say more because unlike for some, KK for SA music never died. And Dhlamini was no hero: he killed his partner.

LikeLike