There’s always been a gentle tug-of-war between the various elements bundled together in the title of the nine-year-old Johannesburg International Mozart Festival (JIMF). Initially, as Artistic Director Florian Uhlig recalled on Sunday, a theme of “Music in Exile” made talking heads and debates on musical discourse prominent. Since then, some programmes have foregrounded the ‘Mozart’, or ‘International’, or ‘Johannesburg’ aspects, while others have offered more of an even blend.

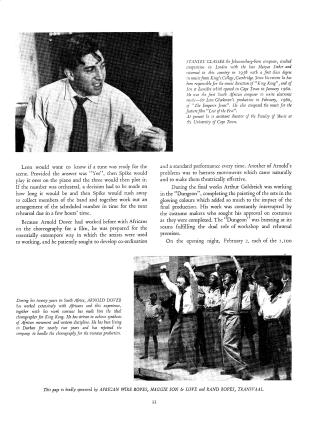

This is one of the blender years, and concerned – as Uhlig also noted – to augment occasions for listening with spaces for active engagement with the making of the music and its makers. Sunday’s Re-Mixing Music at the St Francis of Assissi Church in Parkview provided one of those. Through the facilitation of JIMF’s Composer-in-Residence, Neo Muyanga, three other South African composers, Kingsley Buitendag, Prince Bulo and Lungiswa Plaatjies presented and then discussed, original works that considered the interactions between Western and African musical traditions.

It was, as Muyanga noted in the discussion, a time for “getting away from the binaries” and exploring points of contact, echoes, influences, reactions and conversations. And those conversations, musical and verbal, also provided illumination from a different direction for the decolonisation debate.

Often, musical attempts to fuse or blend traditions end up merely ornamenting the dominant discourse of one tradition with some decorative elements from the other. Writer and musician Amit Chaudhuri, discussing his own context, put it well: “an Indian classical musician moonlighting with Western players: him soloing, representing some so-called immemorial tradition; them adding colour and representing the modern – neither category in itself static, but becoming static in their meeting.”

Such limitation can be reinforced by commitment to the binaries, such as the assumption that no real meeting is possible because, in one of Muyanga’s examples, “African music is said to be circular or cyclical; Western music to be linear.”

But the music presented on Sunday subverted that kind of categorisation. Plaatjies’ Vuma–Ekhaya–Ndiyahamba, for example, (the most extended of the three works) managed to be both circular in its use of traditional sound-cycles, but linear too in (as its title describes) its expression of a musical journey. There was equal interplay, without dilution, between the tones and textures of her voice and bow and the tones and textures of the string ensemble.

And the African elements foregrounded for listeners an aspect of embodiment of the music that can be forgotten when considering Western music. Some elements of African traditional music are always silent: they’re the spaces where the feet of the dancer should fall. Both Plaatjies and Bulo, in the discussion, recounted how movement helps players, especially in their role as healers (which is Plaatjies’ lineage), to enter the mental space the music needs. That embodiment goes further too. Plaatjies’ uncle Dizu (of Amampondo fame), a contributor to both performance and debate, explained how bow-gourds need to suit the breast shape of their female players, and how community midwives can use the vibration of the bowstring like an ultrasound.

In response, Uhlig discussed how the intervention of music industry intermediaries over time had erased that personal bodily connection from the Western musical tradition. Mozart’s manuscripts, he explained, contained minimal instructions. When Mozart wrote them, he was going to be the player and did not need to tell himself how to interpret. The instructions were created as the music was disseminated to other contexts – and we do not know what different variations in mood and feel Mozart may have employed on the same piece, because the instructions have made one mood and feel canonical.

Violinist Waldo Alexander picked up the refrain of ‘lost’ interpretation, recalling his work with legendary bow composer Madosini, where the lack of an adequate notation method meant that the musical moments of those performances, if not recorded, were lost forever. But how to notate? Bulo queried whether and how traditional Xhosa terms denoting musical feel should be translated.

It’s a pity the conversation was too short to explore full answers. Because we do not worry that glissando and its ilk are Italian words. A decolonised musical space might equally easily just use those Xhosa terms and add them to our lexicon and classical culture.

• Neo Muyanga’s own composition is showcased at the JIMF closing concert on February 5 at 3:00pm in The Edge, St Mary’s School. You can also catch visiting UK pianist Joanna McGregor (a former collaborator of the late Moses Molelekwa) on Saturday 4 February at the Linder Auditorium, and pianist Paul Hanmer with guitarist Louis Mhlanga creating music for the 1916 silent movie Snow White at the Maboneng Bioscope on Thursday Feb 2 at 7:30. The full programme is at http://www.join-mozart-festival.org