Thursday 30 April 2020. Myself, McCoy Mrubata, Brenda Sisane and host, Jazz at Lincoln Centre’s Seton Hawkins, discuss the history and distinctive character of SA jazz this evening. The event will stream live on Facebook Live at JaLC’s Jazz Academy page (facebook.com/jalcjazzacademy)

Month: April 2020

Jazz, booze and Freedom (Day)

It’s been an ironic Freedom Day this year. Just over a quarter of a century since our first democratic election, South Africans are once more confined to their homes while troops patrol the streets. This time, though, we’re under the dictatorship of a 120-nm virion scientists have labelled Sars –CoV2: an evil regime that – unlike the previous one – imposes terror and suffering irrespective of race.

The Covid dictatorship, however, still opresses unequally. Under lockdown, people with low or no income are effectively imprisoned in intolerable living conditions: unventilated incubators for all and any infections flying around. Out on the streets, they encounter a still-militarised police force (whatever happened to the demilitarisation promised in 2013?) and an army untrained to handle sensitive civilian interactions. That has fuelled bullying and tragedy, even as the lockdown overall clearly has slowed the pandemic.

But then there’s the issue of the booze ban. Township taverners have lost income, looters have raided liquor stores – and a quite remarkable number of commentators have inexplicably decided now is the right time to romanticise an ostensibly historic “right to drink”. Since booze and music have long been intertwined in the mythology of South African jazz, maybe we should take a long cold draught of reality.

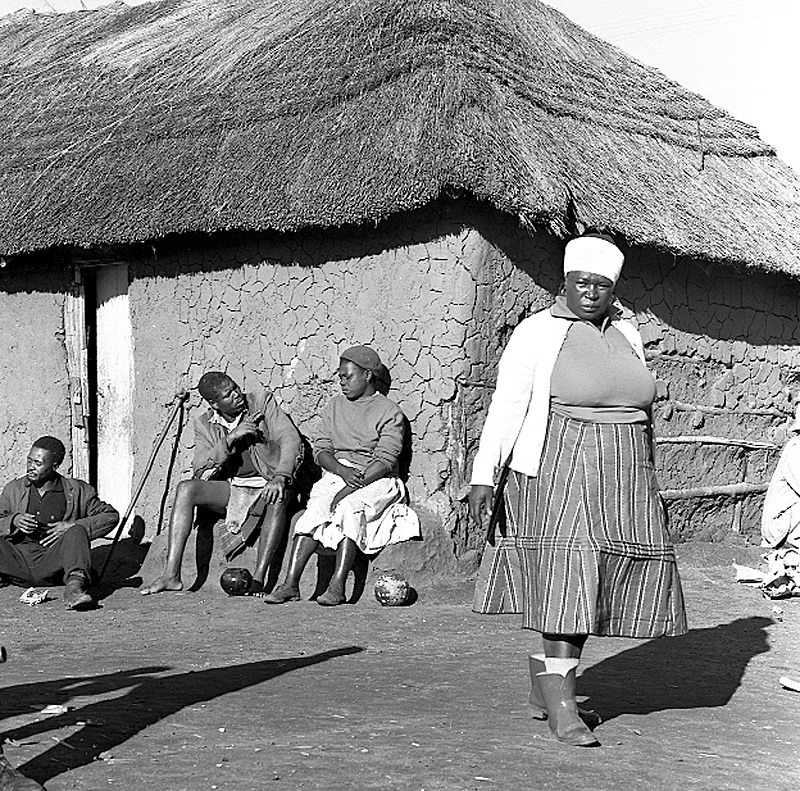

Long before colonialism, rural women were respected for their skill in slow-brewing nourishing, often relatively low-alcohol beverages from natural ingredients. Those drinks were part of the self-reliant exchange economy of local communities, and strengthened social cohesion through the gatherings and ceremonies at which they were consumed. As colonial encroachment and taxes forced men to sign up for mine work, women moved to the cities too, to escape poverty and the patriarchal regimes colonial laws had enshrined. They carried their brewing skills with them to earn an income, and offered migrant workers a taste of home. They rebuilt social solidarity as they developed stokvel-type collective arrangements to source ingredients, caring for children and evading the authorities together.

Traditional brewing built community solidarity

It was unthinkable to successive white regimes that self-reliant social spaces should exist for black workers, or that Africans might form ties of affection or families in the cities. Besides, alcohol was a wonderful instrument for social control and revenue-generation.

Over successive years, an intricate dance between liquor magnates, mining magnates and the forces of state and cities (its early phases well-described by Charles van Onselen in his essay Randlords and Rotgut) used industrially-produced liquor to discipline, subdue and – during the 1970s ‘total strategy’ – seduce working people. (The advertising industry today continues that last proud tradition, reaching into all communities, rich and poor.) They harassed independent women brewers with frequent raids, forcing them to ‘boost’ and speed up their processes, and cater to male customers already alcohol-addicted by company and municipal beerhalls.

municipal beerhall

From the start, the women fought this system. In the late 1920s, the Women’s Auxhiliary of the Industrial and Commercial Union (ICU), brandishing their pounding and stirring implements, smashed the Natal beerhalls. Protests against beerhalls and raids erupted throughout the 1930s and 1940s. Most dramatically, in 1959 in Cato Manor in KZN, a similarly-armed demonstration of African women led by FEDSAW leader Florence Mkhize and ANC militant Dorothy Nyembe forced their way into a beerhall, poured out the beer, smashed the containers, and beat up the male drinkers. They demanded the right to produce and sell traditional, slow-brewed, utshwala. Booze peddled by the authorities, they declared, made their men sick, violent and addicted, consumed wages and destroyed their traditional livelihood.

After 1976, revolutionary township youth torched the taverns distracting their parents from the fight for freedom, while it was often those tavern owners loyal to the regime who kept their licenses – and went on to become apartheid’s first generation of minion councillors.

Young musicians watching and learning from their elders recall the uncles enjoining them: “Don’t do what we do – don’t drink”, but then found themselves playing at promotional gigs where they were too often paid with “a case of the product”.

And here we are today, the fifth most alcohol-guzzling nation in the world, just below our neighbours Namibia and Eswatini, who share much of that history. At every economic level, booze spending strips family incomes. Alcohol contributes to all forms of risky behaviour, violence and road carnage. When the lockdown banned alcohol sales, normally overstretched hospital emergency admission wards emptied.

None of this is an argument for unenforceable prohibition, nor for the pompous officials and cabinet ministers we’ve heard lecturing township adults as if they were children. Enough of that nonsense already. Instead, can’t we reduce the desperation and miserable living conditions that drive escape into alcohol, and create more real jobs as alternatives to kitchen-window liquor sales?

And if we can educate effectively (as we have done) about the threat of a near-invisible virion, surely we can do more effective public health work around alcohol too – for all social groups – and not leave it to toothless, liquor industry-run, “responsible-drinking” campaigns?

Please, let’s stop romanticising the products and practices of big booze capitalism. Let’s be more honest about South Africa’s national drinking problem, and take off the nostalgic spectacles when we look at our liquor history. It wasn’t positive then, and nor is its inheritance today. Depending on intoxication (for cheer, income or oblivion) is the opposite of freedom.

Remembering jazz voices silenced

The late Moses Taiwa Molelekwa would have been 47 today. Every year, there are tributes; this year, jazz fundi and radio host Nothemba Madumo at 4EverjazzSA helms a Zoom tribute today, Friday April 17 at 1600h (if you’ve already downloaded Zoom, sign in with meeting ID 9509735949 ) to raise funds for the music education project bearing his name: the Moses Molelekwa Arts Foundation.

If you can’t make it (or even if you can), remind yourself of Molelekwa’s keyboards, voice and mature arranger’s flair on Wa Mpona https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m7gw5UuNXlM

It has been a sad few weeks for the jazz community in a far more immediate sense, as Covid-19 has swept through the ranks, robbing us of some remarkable talents and repositories of history. Among those we have lost are pianist and patriarch of a musical dynasty that transformed the sound of the late 20th Century, Ellis Marsalis; bandleader, music organiser and longtime Dizzy Gillespie collaborator, pianist Mike Longo; ubiquitous session guitarist (his was the guitar both on Roberta Flack’s The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face and Ray Charles’ Georgia on my Mind) and one of the fathers of the New York scene, guitarist Bucky Pizzarelli, who reminisces about his remarkable life here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=goDqtP4MtqQ

We have also lost two notable collaborators with Miles Davis: on March 31, trumpeter Wallace Roney at 59, and, yesterday, legendary reedman Lee Konitz, aged 92.

Philadelphia-born Roney is best known for his 6-year collaboration with Miles Davis before the senior player’s death in 1991. But the multi-Downbeat Award-winner worked across the jazz spectrum during his 40+ year career, from stints with the Jazz Messengers and Tony Williams to collaborations with Ornette Coleman, with his former wife the late Geri Allen, and with artists from other music genres including turntablists. Sometimes criticised for hewing too close to the Davis style, he preferred to assert that he was very deliberately exploring ways in which the trumpeter’s legacy could be extended without distortion, terming his own approach “straightahead innovative music.”

Roney had 24 albums to his name as leader (most recently the 2019 Blue Dawn/Blue Nights https://www.qobuz.com/ie-en/info/Actualite/Video-du-jour/Wallace-Roney-Celebrates-The-Jazz182287 ), plus film scores and extensive work as collaborator and sideman. The recordings of Konitz – born in Chicago in 1927 – however, go into three figures even before his sideman/ collaboration sessions are counted. Konitz was cool embodied – but it was the edgy cool of Miles, not the bloodless work that has often dominated discussion of the sub-genre. Listen to him talking about the landmark Birth of the Cool album here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QuMIOvqo53s and hear Davis and Konitz working together here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SsuD_1O7IXc

All these musicians have given the world something impossible to quantify: the joy of listening to their music, yes, but also a massive intellectual contribution to shaping the genre. All of them have helped shape the sound our ears acknowledge as jazz, and, by their own innovations, kept the door open for the jazz innovations happening today, not only in America but here too. Even the most senior of them does not belong simply to jazz history, but to its future. It’s that future, in the form of institutions such as the Moses Molelekwa Arts Foundation, that now needs to be nurtured. May all their spirits rest in peace.