You may not yet have read Miles Keylock’s musings on the issues of payments to musicians (http://www.dontparty.com/2016/06/music/conversations-jazz-bar-coming-musicians-paid-rate-masters/ ) If you haven’t, you should: it’s a fine piece of writing. But its content – Keylock’s assertion that young musicians are cash-obsessed and egotistical – as well as the way he frames the debate, have stirred up significant controversy.

Keylock conflates a number of different arguments, and it’s worth picking them apart. But, for me, his framing is also important. It adopts a writer’s voice that has become almost a tradition in much white, male jazz writing but which is not unproblematic. So let’s look at that, too.

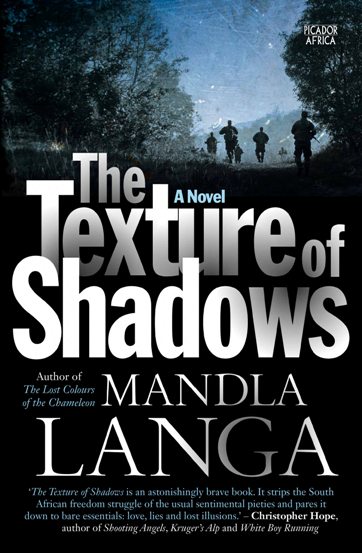

A common misconception is that patriarchy relates only to relationships between men and women. As Mandla Langa illustrates wonderfully in his novel The Texture of Shadows (http://panmacmillan.co.za/catalogue/the-texture-of-shadows/ ) it is also very much about the relationships between men and men, which often overdetermine other gender relationships. Langa’s concern is with political and military ‘chefs’ and their subordinates and acolytes – but you could also extend the paradigm to old-style bandleaders and their sidemen.

But let’s get the straight labour issues out of the way before we go further with that. Keylock’s blog starts with a young musician grumbling about a wage split. He’s going to take home R500. The essay ends with the bandleader gratefully (yes, gratefully) being enlightened by the promoter – the promoter, nogal! – that he should do what the ‘old cats’ did : “[They] didn’t pay their players a salary, brother. They paid…what they’re worth…You’re the leader, right, so lead.”

Leaving the faux-familiarity and faux-hipness of that conversation for later, let’s discuss what a fair labour practice would look like in that situation. First, we all agree there should be more money available to pay good musicians. That there isn’t may be the fault of the promoter, or the weather, or perhaps more broadly of a cultural industry whose political patrons speak tearfully at funerals about how musicians ‘died penniless’ but neglect policy steps including venue subsidies that might just stop it happening.

Whatever the reason, the promoter is the employer, and the bandleader is put, usually unwillingly, in the position of a labour broker. A fair labour practice would involve transparent negotiation at both those levels before the gig happens, enshrined in a written contract that everybody agrees to. Anything else is bound to lead to tears. It’s at that stage that the leader’s share should be agreed – based on multiple possible factors.

Bandleaders may be bigger drawcards than their collaborators – or they may not. They may have put more into pre-organisation and promotion, arranged transport, done all the compositions and arrangements, etc – or they may not. They may be better players – or they may not. Sometimes they’re the one who, in Keylock’s charming and (perhaps unwittingly) deeply gendered phrase “plays like a poes”. In any case, jazz is a collective effort and even a brilliant improvising leader only shines on the stand because, in trombonist George Lewis’s phrase “the rest of the band has got their back.” How those issues should be dealt with in terms of respective payments – there’s nothing automatic about it – needs to be discussed transparently, agreed democratically and ideally signed to. That’s real professionalism.

Many bands I know already work like that. (Bheki Mseleku – cited erroneously by Keylock as an old-style leader – regularly gave up his share so bands he led could eat; I saw it myself in Botswana.) Those bands that don’t, need to get with the programme fast.

The circumstances in which labour should gratefully accept advice from an employer about payment practices as Keylock describes are few. Often, it’s a divide-and-rule negotiation tactic, and that is exactly what has happened here, with Keylock’s prose setting some selective quotes from “older” musicians against his characterisation of “younger” ones. In the face of philistinism, limited resources and low pay, jazz workers needs to be united.

Yes, some of those old bandleaders did – and some still do – bully and punch out their younger sidemen. They sent the youngsters out to buy bottles and drugs and procure sex for them; or they sexually harrassed them; or they turfed the youngsters out of their rooms to accommodate binges and orgies. But first we should remember that what becomes legend is the unusual, not the usual. “OK the bandleader booked us into a hotel. He organised food for us, we all had a good night’s sleep, and then we left ridiculously early to get on the road” does not make a very exciting story.

Second, what was and is, is not necessarily a model for what should be.

Then there’s the false counterposition of “cash” and “creativity”, as though the two cannot coexist. The privileged often romanticise the poverty of others – you know: “Edith Piaf was so great because she grew up in the gutter.” No, Piaf and many like her might had been even greater if they had grown up more softly, and not been driven to drink and drugs to dull the pains of want and exploitation.

And that takes us on to the framing of the story. The larger-than-life old jazzman, with gargantuan appetites and sordid bad habits shaped in the (profoundly stereotyped) “ghetto”, caring nothing about other people, who makes jazz great because he (it’s always he) is such a towering heroic soloist, is the stuff of white critical myth-making about black jazz. If you want to read the whole story of that, there’s no better book than John Gennari’s Blowin’ Hot & Cool (http://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/B/bo3752833.html )

That older generation of largely American and British critics shaped a voice and outlook that many of their successors, including brilliant writers such as Geoff Dyer, have subsequently adopted. It became in many contexts the voice of the genre. And it’s problematic:

“Dyer calls Jones ‘Elvin’, calls Coltrane ‘Trane’; this sense of false intimacy is significant. Dyer is the author of But Beautiful, from 1991, a fictional gaze at classic-era jazz greats, in which he writes about ‘Lester’, ‘Bud’, ‘Chet’, ‘Ben’, and, for that matter, ‘Hawk’ and ‘Trane’. He writes like a club patron who insinuates himself into the company of the musicians between sets, extracts their confidences, observes scenes of intimate horror, and then passes them along—using first names and nicknames—as if to flaunt his faux-insider status. But, when the musicians are back on the bandstand, he never lets them forget that they’re there to entertain him.” That’s Richard Brody in the New Yorker (http://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/coltranes-free-jazz-awesome ) commenting on Dyer’s New York Review of Books trashing of Coltrane’s album Offering: Live at Temple University. (http://www.nybooks.com/daily/2014/10/04/catastrophic-coltrane/ ) Dyer is a magnificent writer. But he’s chosen to put himself in that place: the anorak-wearing fanboy worshipping dark, exoticised myths he himself has created, and becoming tetchy when the real human beings on whom they are based don’t perform to order.

Like, for example, stepping out of myth-land to care about whether they can feed their kids.

Let’s end with stories of an old-style South African bandleader, reedman Dudu Pukwana. He did sometimes get angry with his sidemen and chase them off his stage. I remember those evenings, at a little theatre in South London: I was there. By the interval, Pukwana would have hugged everybbody and reconciled. Exile was a fucker; he was under stress, and shit sometimes happened. But the saxophonist had politics. He always tried to pay his musicians fairly, and I’ve sat beside bar-table discussions where he debated with the band how the split should go.

Let me tell you about a college gig where Pukwana was a sideman, with another old-style South African leading. Pukwana found out the other guy had lied about the fee. “Show us the cash,” he demanded. “Just show us the cash.” When the rest of the band joined in, the lying leader eventually complied. Pukwana shook out the bag (it was a door take) and ostentatiously counted, first the band members and then the notes. He created five equal albeit pathetically small piles, took his own, and stood. “To me,” he said, “that seems fair. And as for you, you lying mofo, I will never, ever work with you again – not because the money is small, but because you weren’t straight with us.”