It’s nice to have readers. Not only do they get the metrics up, but often they suggest challenging new themes for me to write about.

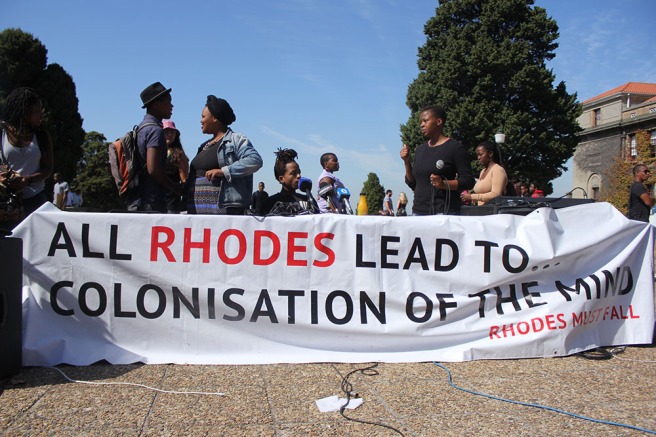

Now one – a South African student overseas – has raised a long-overdue question. While #RhodesMustFall extensively explored the general question of white ideological domination of South African universities, the campaign hasn’t, as far as I know, situated the question specifically in the music faculties. My correspondent asks: “Why is it that at the three major jazz institutions in South Africa – UCT, Wits and UKZN – combined, a majority of the lecturers teaching jazz (a black-originated music) are white? And in every one of these places, the drum teachers are white, so people come from other parts of the world to learn South African rhythms from…”

It’s a fair question, but a big one, and probably best disaggregated and its components discussed separately. It interrogates the nature of universities and their definitions of who is a scholar; whether a music genre can be said to ‘belong’ to any particular group – and whether race is the only ground on which university jazz faculties could be perceived as exclusionary. So this is quite a long read…

Universities: open doors or close-mesh filters?

It’s worth pointing out that universities have always, and almost by definition, exhibited exclusionary behaviour. The claim is that the exclusions have purely meritocratic grounds – “We want only the brightest and best” – but that has not always been the case, not since Sokrates mentored the sons of free Athenians, while their slaves carried their scroll-cases.

Class, religion, race, language, gender…universities have historically found a myriad of grounds – formal and informal – to filter from among the equally able those their establishments have defined as “our kind of people”. The more unequal the society, and the less efficient the counterbalancing mechanisms such as scholarships and grants, the smaller the chances are of those who are not “our kind of people” even making it to the filtering-gates. Network studies calls this preference for “our kind of people” homophily, and we’ll return to it later.

It starts at undergraduate level and the career-path of a researcher and teacher in higher education is impeded by even more filters.

Some of those are, indeed, meritocratic. Whatever his or her subject matter, from architecture to zoology (and including jazz), a scholar must achieve a doctorate, undertake research, publish in accredited journals and generally be acknowledged by his or her peers to have made an original contribution to knowledge in the field.

The contextual enabling factors, however, still demand resources as well as merit. It’s a lonely, poorly-paid path that can take close to a decade. It’s hard for an aspiring scholar with difficult home circumstances such as needy relatives or an unsupportive partner. It’s harder for scholars based at an under-resourced institution with small postgraduate cohorts, where heavy practical teaching responsibilities leave little time for research and publishing. It’s much harder in a field where there is constant tension between very different but equally legitimate definitions of ‘original contribution’ – between, for example, actually blowing original solos, and analysing other people doing it.

Much respect, then, to those jazz faculty members from whatever background who’ve made it into university teaching.

Turn the lens on South African universities in general, and the record on racial transformation at postgraduate levels is spectacularly unimpressive. Despite a massive increase in black undergraduate enrolments since 1994, the first-degree graduation rate at the country’s 23 public universities reported by the Department of Higher Education in 2013 was around 15%; that for Masters students 20% and for Doctoral students 12%. White completion rates, the Council for Higher Education told a newspaper, were “on average 50% higher than African (black) rates (…) only 5% of African and coloured youth are succeeding in higher education (…) strongly influenced by the socio-economic background of individuals…” https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2013/aug/22/south-africa-universities-racially-skewed

It is from within that tiny 5% – across all subjects, including jazz – that potential university teachers of colour under current qualification requirements, have to come.

The impact of homophily

But there’s more to the story than an inadequate supply of candidates. A recent scholarly paper, Including Excluded Groups: the slow racial transformation of the South African university system, by Barnard, Cowan et al. (http://econpapers.wiwi.kit.edu/downloads/KITe_WP_89_modified.pdf ) points out that homophily can still limit the appointment of faculty of colour by white-dominated hiring committees, even in the presence of formal affirmative action measures. Appointing in one’s own (white) image has feedback effects, limiting the role models for aspiring scholars of colour considering an academic career, and contributing, as other studies cited have found, to a profoundly alienating environment. The study’s mathematical models suggest that even a small improvement in hiring practices could make a significant contribution to transformation, albeit within an inherently slow process and a resource-poor national context.

In a field such as jazz, however, perhaps the process need not always be quite so slow. From Gramsci through Foucault to Julia Kristeva and more, philosophers have interrogated and deconstructed the traditional perception of the intellectual as someone who creates high-order understanding that stands above affiliations to enhance a neutral body of universally valuable ‘knowledge’. We now acknowledge that scholars exist within, and operate in relation to, professions, institutions and ideologies. As well as the ‘traditional’, there are ‘organic’, ‘specific’ and ‘dissident’ intellectuals. Many black South African jazz players still living have already made significant original intellectual contributions over decades via musical technique, teaching, organisation, and imagination. They are already organic intellectuals from within jazz music. Why, then, is it so impossible to devise paths to professorship beyond the traditional for them?

Except, of course, that any hegemony invariably naturalises its own traditions as universal standards…

Does it matter if it’s black or white?

At this point, somebody often dismisses the transformation argument in relation to jazz education with a declaration that the music is “a universal language”. So long as they are skilled, enthusiastic and supportive, does it really matter whether the teachers are black, white or – a favourite kind of liberal addition – sky-blue purple? (Of course, such nonsense colours as sky-blue purple do not describe real people with histories and experiences that might be relevant to the argument.)

Jazz began its life as black music: in Africa and through the African-American experience. It was created by musicians with big ears. Everything from the European dances of the plantation masters in the American South, to the British military bugles and Scottish pentatonic hymns of colonialists in South Africa, to the very sounds of nature, got filtered through those ears and transformed into a unique sonic landscape. But as scholar Lewis Porter has said, being so creatively open to ideas from everywhere “doesn’t make [the music] non-black.”

The quote is from a column on the topic by one of my favourite jazz writers, Nat Hentoff (http://jazztimes.com/articles/18103isjazzblackmusic), and he goes on to quote Bird, Monk, John Lewis and others asserting that anybody who genuinely feels the music can play it, without barriers of origin. That’s certainly true, and heart-warming, and wonderful – but it is only part of the argument.

Music shows us a social and historical landscape as well as a sonic one, including how it is produced, received, taught and learned – and what exactly is taught and learned. If universities are to grow great jazz players who genuinely feel the music, they must take some of that on board too.

Salim Washington, American-born Professor of Music at UKZN, points out that a teaching approach that irons out much of the layered identity of jazz, teaching it simply “as a step-sister to Western Art Music”, loses a lot. “The conservatory method reigns supreme, with all its aesthetic and practical biases. The pedagogical method of the jazz bands, big bands, and black churches is completely ignored. The cultural values and philosophical underpinnings of the music are never discussed, let alone modelled and taught…the issue is: is black music being taught from a black perspective?”

That “step-sister to Western Art Music” idea has haunted South African jazz history. The ideologists of apartheid represented jazz successively as a Western music appealing to the basest instincts of ‘traditional’ Africans; then as something too sophisticated for them to grasp; and then as something they succeeded in only by “learning from whites”. We live within the tatters of our history, so the current school music curriculum sets up jazz as a parallel stream to Western classical music, with both wholly discrete from ‘traditional’ music. Such ideas may well waft around some departmental appointment boards too.

The question of who should teach drum rhythms underlines these issues even more emphatically. As Washington observes: “The drum is a sacred instrument. It is the conductor of black popular music and of jazz: the instrument that black jazz musicians invented. Its invention is also connected to its function in the rhythm section – another invention of black jazz musicians. As such, the most sublime aspects of the music are most often created with the drums. It’s a problem if the instructors of the music simply see it as another instrument with which to gain technical proficiency.”

We’ve already seen from the research that the alienation often felt by students of colour in white-dominated jazz faculties can deter potential scholars. But the debate should not be about whether Professor X is a racist (fire him!) or Professor Y is a good person (promote her). It’s about ensuring that university jazz teaching conveys the full richness of the intellectual capital of jazz, and, in this country, of the South African jazz tradition too. That – given the current impoverished demographics of South African music faculties – means we need more jazz teachers of colour.

And who else is missing?

Look at the personnel of South African jazz departments, however, and another characteristic quickly becomes apparent. Not only are the faces predominantly white, they are equally predominantly male –even more heavily so when vocal practice lecturers are removed. We still suffer the continuing – and international – assumption that “women instrumentalists… still have to prove that they have the “balls” to be authentic jazzmakers. Oh, there are interesting features, sometimes sections, in jazz magazines on women in jazz, but the attitude is often that of noblesse oblige, like making sure there are enough blacks on television sitcoms.” That’s Hentoff again (http://jazztimes.com/articles/19661-a-thrilling-big-jazz-band ), drawing just the right parallel. For many, very similar, reasons it matters just as much that jazz faculties often present as boys’ clubs, as well as white clubs. It erases parts of the history, and filters potential diversity from the future. Historian Linda Dahl, in her 1984 book Stormy Weather (https://www.amazon.com/Stormy-Weather-Music-Lives-Century/dp/B00AK3IT3W ), put it like this:

“…Full of masculine metaphors, the sense of fraternity or of a male club is everywhere evoked [in jazz]…the qualities needed to get ahead in the jazz world were held to be ‘masculine’ prerogatives: aggressive self-confidence on the bandstand, displaying one’s chops, or sheer blowing power; single-minded attention to career moves, including frequent absences from home and family. Then too, there was the ‘manly’ ability to deal with funky and often dangerous playing atmospheres…A woman musician determined not to be deterred … often paid penalties designed to put her in her place – the loss of respectability being high on the list, as well as disapproval, ridicule and sometimes ostracism…The assumption about women in jazz was that there weren’t any, because jazz was by definition a male music. Therefore, women could not play it. Therefore, they did not do so”

We already know from research that women perform better academically when other female role models are present. CHE figures, again, (http://www.che.ac.za/focus_areas/higher_education_data/2013/participation) demonstrate a fall-off in female participation at the postgraduate level that begins the path to teaching posts. Where students of colour experience alienation, exclusion and racism, female jazz students experience alienation, exclusion and sexism (See, for example, Dr Ariel Alexander’s findings from her 2011 research at http://www.jazzedmagazine.com/2693/articles/guest-editorial/guest-editorial-where-are-the-girls/ ). Aspiring black female jazz scholars encounter both.

And so..?

One of my scarier findings in researching this piece was that SA university jazz departments look somewhat more representative of the country than certain other subject areas. Nevertheless, their limited diversity has consequences very similar to those in any other un-transformed part of higher education. Homophilic appointments perpetuate the old demographics. Black and female students find too few role models. The scarcity of postgrads of colour means those who make it that far are trapped by heavy teaching and supervision loads, which hampers their ability to publish and progress further towards heading up their departments.

The resulting music will not be everything it could be . As Washington observes: “I have encountered black students doing the most offensive cornball shit because somebody told them that was how to swing – Lord have mercy!” Or, as reviewer Richard Brody commented, in his excoriating review of that whitest and most macho of sagas of jazz education, the 2014 movie Whiplash: (http://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/whiplash-getting-jazz-right-movies ) “…Buddy Rich. Buddy fucking Rich.”

I advocate for an integrated educational system. While I am grateful for my formal education at UCT, I am at least equally (probably more) greatful for my informal and personal education I received through learning from and playing with the greats of South African Jazz. Bheki Mseleku, Hotep Galeta, Zim Ngqwana, Feya Faku, Robbie Jansen, Herbie Tsoaeli, Louis Moholo and Lulu Gontsana, Wintson Mankunku Ngozi and others – some have already passed away – have guieded me to develop my own unique style while being firmly rooted in the South African musical tradition.

Through my studies abroad and my engagement in international colaboration I have learned that these are the masters that are know as representatives of South African Jazz. Sadly, the very people known as the greatest South African Jazz musicians feel that their contribution to our music is being overlooked on a local level and rendered irrelevant to higher education.

Musical education suffers from the crude misrepresentation of black South African Jazz muscians as students and teachers in our Universities. It is striking that the formal institutions miss the oportunity to take the legends of South African Jazz on board, give credit to the rich musical roots in our country and cherish those who have kept this spirit alive while developing the music further and taking it out into the world.

As I said, I advocate for a combination of formal Jazz training (American syllabus) and passing on the music on a personal level. As I know from my own experience: nothing compares to learning directly from the masters.

LikeLike

The author as is often the case with verbal criticism leveled at music, is likely a failed musician – the fool waxes lyrical about how more is learnt on the street in jazz.. So is the case with every discipline from bio chemistry to law to architecture to archeology to medicine – nuclear physics .. You only really learn when you are in the field. University is the intellectual space (after school) in which to tackle the thought processes needed to engage the disciplines. This is not solely reserved for jazz… That all said.. In music – chops, knowledge and proficiency are needed to play the instrument that is chosen to express creativity. There is nothing more frustrating than listening to talent struggling to express itself through one of the Eurocentric instruments like piano, sax, trumpet…. because of an absence and disrespect for the required skill set that predates the chosen style.

I am afraid our author is somewhat misinformed – he has forgotten to acknowledge that jazz is an African American music – a fusion of two disparate cultures -African and European – without the latter their would be no harmony and no musical instruments.. But this does not fit his tired and wordy narrative.

All said – I see there is a lot of interest and research currently going into Bheki Mseleku – a name rarely mentioned by the local music critics especially the ones who love to wax lyrical about African jazz heroes.

LikeLike

The author of the comment to which i’m responding is likely an old white man, who thinks he’s a serious cat, he could possibly be a teacher in one of the country’s colonial education institutions. If he did it would be very ironic that he has immediately assumed the author of this article is a man – ironic because it reflects the sexism that pervades sa music schools to which the blog author made reference. And blatanly his racist understanding of African history leads him to believe that there were no musical instruments on the continent.

Your comment is boring and defensive.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Superb article!

LikeLike

Well done. You have succeeded in bringing racism into the SA music teaching scene. Judging whether or not someone should teach based purely on the colour of their skin is racism, pure and simple. Use whatever semantics and big words you want. This is a racist piece and I hope others are not afraid to condemn this sort of racism, regardless of how it dresses itself up as intellectualism.

LikeLike

Dear Elle

Read a book on the history of racism, you are quite confused about what it is.

Sincerely,

Black Jesus

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course we need to appoint black faculty at historically white South African institutions. However, ‘Who should teach jazz?’ is irrelevant when asked from the perspective of white versus black. More relevant is to ask why are highly trained black musicians overlooked for higher academic positions? The simple straight forward answer is white jazz faculty feel threatened, it upsets the the white boys club comfort zone. That South African musician Hotep Idris Galeta, a tenured jazz faculty member at a prestigious US institution, was not offered a position on his return to is homeland in 1991 by a South African university, although incomprehensible, strongly confirms the insecurities that still haunt too many white folk at places like UCT and UKZN. This articles again raises the question of ownership of jazz as an art form. Without the black experience of enslavement and oppression in the Americas, jazz would not exist. The search for physical and spiritual liberation is the essence of jazz, however it is Search that can be pursued by any man or woman, black or white. The central issue is access to education and who gets or is denied access.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great article. Sad about some of the comments that are immediately defensive.

LikeLike

I think the article written is not really well informed and some of the comments are not constructive either. Mr Miller suggests Hotep Galeta should have been offered a position. I understood he taught at Fort Hare where he was given funds to set up a studio. What happened to that studio? Also I believe he ironically held a masters degree in jazz from UCT. What about Zim teaching at UKZN? Isn’t he black? Didn’t he study under Darius Brubeck? Salim Washington isn’t even south african so how relevant is that? It is such a complex issue. I was a student at UCT and am grateful for the knowledge it gave me and the opportunities I now have, scholarships, funding, overseas exposure. UCT students win all the prizes and people are just jealous. Look at Judith Sephuma, Selaelo Selota, Musa Manzini, Bokani Dyer, Nomfundo Xaluva, Darren English…. some of these were my contemporaries and we just practiced and did the work. Where there is a will there is a way. Yes some classes seemed a waste of time and others I have mostly forgotten, but it was a space to be together and be influenced by our peers, to be competitive and discover ones own influences and angles. Times are changing and yes we need to mould with the times but lets not discard the good that has been done, nor destroy and replace it with another failed system like outcomes based education and wait to see. Lets be sensible, not too emotional and most of all respectful.

LikeLike