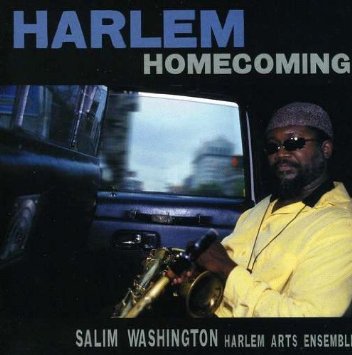

Saxophonist and composer Salim Washington was kind enough to grant me an interview prior to his gigs at the Orbit this week. Part of that interview was published in today’s Mail & Guardian as “Reedman Blows Fire and Tears” (http://mg.co.za/article/2016-01-21-reedman-blows-fire-and-tears). But it was a wonderfully extensive conversation, which I had to truncate shamefully to fit onto a print publication page. Here’s most of the rest of that conversation…

GA: Tell us a little about how you got started in jazz?

SW: I decided to be a dedicated musician after a friend shared a John Coltrane LP. I was a teenager in high school, already deeply involved in music, leading my own band and performing in restaurants and for parties, etc. I was at that time a fledgling jazz musician, more steeped in gospel and R&B. But hearing Coltrane sparked a desire to be as good as I could be. There was an example for me of blackness and hipness and spirituality that I didn’t understand intellectually, but could immediately feel that it was pointing out the path for me.

Playing popular music was fun, of course, and meaningful for me. But as a trumpet player (my first instrument) there was limited intellectual engagement in most of the roles that I had to play. Maybe this is why I very early on became a composer. Jazz allowed me to have the funky soulfulness of vernacular musics, to try to be cool in the non-superficial sense, but also allowed me to stretch intellectually and spiritually as a musician and as a person at the same time. It was the perfect music for me.

When I was a trumpeter my brother, who also played the trumpet, had my instrument, and Detroit being what it was, someone jacked him and took my trumpet, which my parents couldn’t afford to replace! I began playing the piano and when I first started as a bandleader it was on the piano. My flute player was jive, didn’t practice and in frustration I demanded that she give me the flute and I figured out there how to play the melody to That’s the Time by Roberta Flack. The girl then decided to give me the flute. The flute led me quickly to the saxophone. It seems to be able to bear the rather philosophical bent that I was developing. One of my main influences was the great Rahsaan Roland Kirk, and his vision was performative and compositional and political and spiritual all at the same time. This combination made it natural that he play more than one reed instrument, and I followed suit without really realising it. The oboe came and now the bass clarinet is something that I have become obsessed with. I had previously been afraid of it because of the daunting example of Eric Dolphy, but I am getting past that, thankfully! Dolphy and Rahsaan both say things on the flute that other people can only say on saxophone, so I have become a dedicated flutist. That other great multi-instrumentalist Yusef Lateef, was from my neighbourhood and we even went to the same school. He was another model and led me to the oboe.

GA: Why have you decided that now is the time to lay down your first album with a South African outfit?

SW: Why record now? For the first part of the answer, four words, Dalisu Ndlazi, Nduduzo Makhatini. What I mean is this, there are in Durban only three bassists who play the upright bass; more in Joburg and Capetown, but here in eThekwini, only three. Dalisu is a fearless and very musical bassist who always puts his hipness and emotions into the music. Nduduzo is very similar in that he never sacrifices soulfulness to show off his chops, and like Dalisu he is emotionally connected and spiritually gifted as a musician. These two musicians in particular have touched me musically and make me able to be me musically. That is, when I make a gesture they understand my language and I don’t have to explain to them how to compliment it. Rather, they intuit how to make it better. That is rare, and so now that I am experiencing it my music is coming alive in the ways that I intended and I need to document this and be able to present it to the world. I am playing with a host of fine musicians, but am only highlighting these two because they have inspired something in me. Ayanda Sikade is a real jazz drummer and I love his precision and energy. The rhythm section is 80% of the music and so these three musicians make this recording possible. Trumpeter Sakhile Simani and saxophonist Leon Scharnick were my most accomplished and talented students when I first came to SA as a Fulbright artist/scholar. I performed with them then, and now they are even better.

Another reason that this is the time to record is that I believe I have learned something from my three years here in SA. I am still who I am, of course, but now I have been invited into the culture and have a better understanding of the rhythms of SA life. This is difficult to articulate, because it’s not like I am trying to play maskandi or mbaqanga, though I listen to it and study it. Just be influenced by it and let it expand my jazz articulations. One great experience I have had in this regard is playing with Mandla Mlangeni, whose compositional and performative aesthetic is quite close to my own in certain respects, but filtered through his circumstances and experiences, something that is shaping my resolve in the direction that my music is heading.

GA: You’ll be working with multiple instruments, voices and poetry in this project? It sounds like you are envisaging a large sound palette…Why is that needed?

SW: Yes, I need a larger sound palette for what I am trying to do. I am using multiple horns on the front line, Sakhile Simani on trumpet and flugelhorn and Leon Sharnick on alto sax and bamboo flute, along with my tenor sax, flute, alto flute, bass clarinet and oboe. Also, I am using voices, and I have to say that I am influenced by Tumi Mogorosi in the ways in which I am using them. I have also commissioned a poem by the great Lesego Rampolokeng. I need all of this because the world we live in, the particular society that we are existing in has brought certain ruptures in our beings that demand expanded expression. The same old thing is not enough, hipness is not enough. I believe the prophetic voice is called for here. I am following my compositional hero Charles Mingus here.

Two events in particular have caused me to write and rethink aspects of music: the xenophobic attacks and the Marikana massacre. For the first I have composed Imililo, which is Fires in isiZulu and for the second Tears of Marikana (hopefully a poetic resonance with Max Roach’s and Abby Lincoln’s Tears for Johannesburg written after the Sharpeville massacre. These two events, I think, point out so much that is wrong with the neo-liberal consensus that the “new South Africa” is supposed to represent. It points out how deadly capitalism always is, but especially the hyper-racialized capitalism that has shaped our country for centuries. While giving the franchise to black people is a step in the right direction, it does not represent freedom or reparations for black people. These events also show the extent to which black people can participate in the policing and oppression of other black people –nothing new, but rather spectacular in these instances. Artists must respond to this scenario which happens in less spectacular ways everyday here in Mzansi. I am trying to do my little part with my music to think and activate on these issues.

GA: Please tell us more about these new works.

SW: Imililo represents the horrible violence of burning a human being, of killing persons and destroying their attempts to make a livelihood because of frustration and perhaps the consequences of violence and deprivation haven been visited upon those who participated, or who watched, or in other ways condoned it. It is also a dirge for what is lost in our collective souls when we allow this to happen. Remember, this is not the first time. There was a similar outbreak right before I came to SA the first time. So, nothing was done to stop it from outbreaking again. Not that time, not this time… The voices are very necessary to bring the sense of the human urgency in all of this, and the multiple horns as well.

Tears of Marikana is in three parts: Blues Preparation, Engagement/Confrontation, and a third part yet to be titled. The first two movements have written music and improvisation, but the third part is improvised, as I do not yet have a definitive way to characterise what happens after the conflagration. This is an unfinished issue: when billionaires head a company in which the workers live in shacks and then murder them when they go on strike, not for a king’s ransom but for a living wage. And not only the self-identifying capitalists, but the state and even a highly placed erstwhile unionist participate. The situation can hardly be exaggerated. Lesego will give us a poem for this. His aesthetic and his oeuvre are both outstanding and show that it is he who has the voice and the perspective to give us words on this continuing tragedy.

GA: How do you approach composing? What begins the process – an idea; a melodic theme; or what, and how do you then flesh it out through arrangement and selection of players?

SW: My compositional process is somewhat varied. I usually compose from the piano, and lean very much into harmonic motions, but as I get older I am coming more from the melodic side. I am also learning that simplicity is a divine thing in music – not simplemindedness but simplicity. On a few occasions music has come to me in dreams. But usually it is an emotion or feeling that drives me to composing.

An example would be Imililo When I saw the images on the television of the violence and carnage I could not sleep. It really bothered me, and the next day came and I still couldn’t sleep. So, I took my horn and tried to just let something out to allow me to come back to myself so to speak. And the dominant opening horn lines came to me. I then arranged it for six horns, ranging from tuba to flute (shame, I can’t afford this configuration in Joburg). I added voices to the mix and conceived of a mosaic in which strength and forcefulness co-resided with absolute terror and horror. I realised that in addition to the march-like forceful passages, I wanted atonal passages of ‘ugly beauty’ (to borrow from Monk). This work has multiple sections, so there are also sections that are pleas to our humanity to consider what we have done, what we have lost, what we could imagine, a dirge. There is a yearning for peace as well, which is also muscally represented at the closing of the composition. Right after the atonal soli section where the horns and voices are in unison the solo begins. I have chosen Leon Sharnick to do this solo, because he understands how to scream musically. This kind of urgency is not always found in SA jazz but Leon, who is a graduate of Zim Ngqawana’s band (as are our excellent drummer Ayanda Sikade, and Nduduzo), understands the connections between the consonant and dissonant sides of jazz expressions and is a really fine alto saxophonist to boot. For this piece I decided to use Tumi on the drums because of his creativity and constant shifting of the box in his musical thinking. He uses silences very well also – quite rare for a drummer. For that reason I have also decided to use Tumi on Tears because silence is a big part of the musical mosaic for this kind of meditation.

GA: Your music doesn’t shy away from addressing political issues. How do you see the relationship between music and politics?

SW: Well, my own first forays into performing music were when I was very young: about 12 or so. I was playing with older musicians who were already listening to Bird and listening to the Last Poets. This was the tail end of the Black Arts Movement and the Black Power movement. So my musical consciousness as a performer was always in the context of trying to fight against injustice, trying to elevate the consciousness of the people, and imagining the need and outcomes of revolution.

Even before I was a performer I was playing music and my initial musical consciousness comes from the black Pentecostal church. In this context music was our world, our strength and power. Through music we were able to call down the Holy Ghost and transform our beings as the nobodies of the world, into Saints of God. People would speak in tongues and dance and shout, and through this would be revived, would be energised to enact the paradigmatic acts of our heroes and gods. The discourse about this was quite impoverished, but the enactment of it was very rich and it has made an indelible imprint on me in terms of what music is and what music is for.

As a young man in college, still a teenager, [late baritone saxophonist] Fred Ho and I were political organisers both on and off campus. We were engaged in movements in the black and Asian communities in Boston’s Roxbury and Chinatown. These movements always involved music and poetry, and we were regulars on that scene both as performers and as organisers. This allowed me to give expression to the consciousness that had awakened earlier when I was still a boy. My parents had always talked to us about our family’s history and the racial and class oppression that we had suffered and were still suffering. They did not have the Marxist analysis or anything like that and were not part of the social movements, but they were proud black people who taught us to be proud and to never cower before white folks or anyone else.

As i developed as a professional musician many of the artists that became my models – Archie Shepp, Coltrane, Mingus, Pharaoh Sanders, Stevie Wonder, Rahsann Roland Kirk – were visionaries and makers of revolutionary music. It seemed that in fact their orientation was not an accoutrement, but part and parcel of the power of their music, and the evidence of their excellence and consequent superiority seemed obvious to me as a young musician.

GA: Another aspect of your work is an interest in linking music with other forms of creativity such as visual art and poetry. How does that fit the vision?

SW: Yebo, the arts are quite permeable for me. Again, my model is the pageantry of the storefront churches in which I grew up and where I found the meaning of music As much as the choir was important, it was not a performance per se, but rather worship. On a more prosaic level it was a skilfully coordinated multi disciplinary, multi-faceted affair: the pageantry of black folks, dressed in their finest and on their best behaviour, combined with poetry and music/speech oratory that was part of the black homiletic style. This included the call and respond with the organist, and with the congregation and was carefully worked up into the ferny of the holy shout. Thus, poetry, costumes, oratory, music and dance were all working in tandem to create a sacred event and space.

My mother inculcated a real love of reading in me. The African American writing tradition is profoundly marked by African American music, and virtually to a man and woman all the major writers of our tradition were consciously using our music as either inspiration or as a guide to their own work. The musical organisation that jazz musicians invented has taken over the modern world and quite often it is in combination with other artistic expressions. Sometimes the technical difficulties of our disciplines can make us blindly pursue the science of the art, but the art of the science makes it mandatory to be open beyond the boundaries of discipline.

At the Orbit I am including poetry and voice, both as instrument and conventionally in singing per se. I need the human voice for the import of this music. It points us more directly into the human dimension of all of these ideas and structures. My collaborations with vocalists have been sporadic mostly because I enjoy vocalists who are musicians as well as singers, and sometimes those are in short supply. Ditto with poets, there are rich, rich poetic traditions here in SA, but the best is not always in English. As an Anglophone I have been so happy to find Lesego who is not an African American wannabe, who is not a derivative spoken work artist, etc, but rather a true artist who has used his talent fearlessly to tell the truth and who has combined high artistic qualities with his fire. Perfect for this project!

GA: Salim, apart from your role as Professor of Music at UKZN, please update us on your other playing, composing and recording activities. What else have you been doing, and what’s next?

SW: The last 3 years. I’ve been involved in the Jazz Composers Orchestra Institute, an initiative of the American Composers Orchestra. It was an intensive workshop for jazz composers who want to write for the philharmonic orchestra. One exciting thing that came out of that experience is that one of the composers there wrote a concerto for double bass and tenor sax with me in mind, Voyager: Three Sheets to the Wind. I have performed it with him and now it has just been released as a CD: David Arend, Astral Travels, on Navona Records, featuring Salim Washington with the Moravian Philharmonic Orchestra. In June another CD will be relaxed that features two compositions each by five composers who were also associated with the JCOI. We are called The Alchemy Project and our debut CD will be on ARC and called Further Explorations. It is also my hope that this year will see the release (finally) of my trio CD, Dogon Revisited on Oliver Lake’s label, Passin’ Thru.

I’ve started a student band, or rather a band comprised of students, called Give it Horns, a decision to teach the old fashion way, by mentoring on the band stand in addition to my varsity teaching. I am quite excited about the results: the young people are amazing. You heard two of them, the bassist Dalisu Ndlazi and the guitarist Bethuel Tshoane when we played last in Jozi.

I did a stint as a Fulbright Specialist at the Conservatorio Nacionál in Bogotá, Colombia, where I helped bolster their jazz program, delivered classes and two lectures, various interviews and performances. I got the students to play Cal Massey’s master-work, The Black Liberation Movement Suite, among other things. I’ve also been to Ningbo in China, although there were rather fewer jazz cats there and I had to travel out of town to find them.

As for future plans, my dream is to have a jazz orchestra, a symphonic orchestra, a South African choir, a Brazilian percussion ensemble, a male and female poet and dancers all performing this music together. One day, one day…

GA: Thanks Salim for sharing these insights with us.

SW: Thank you